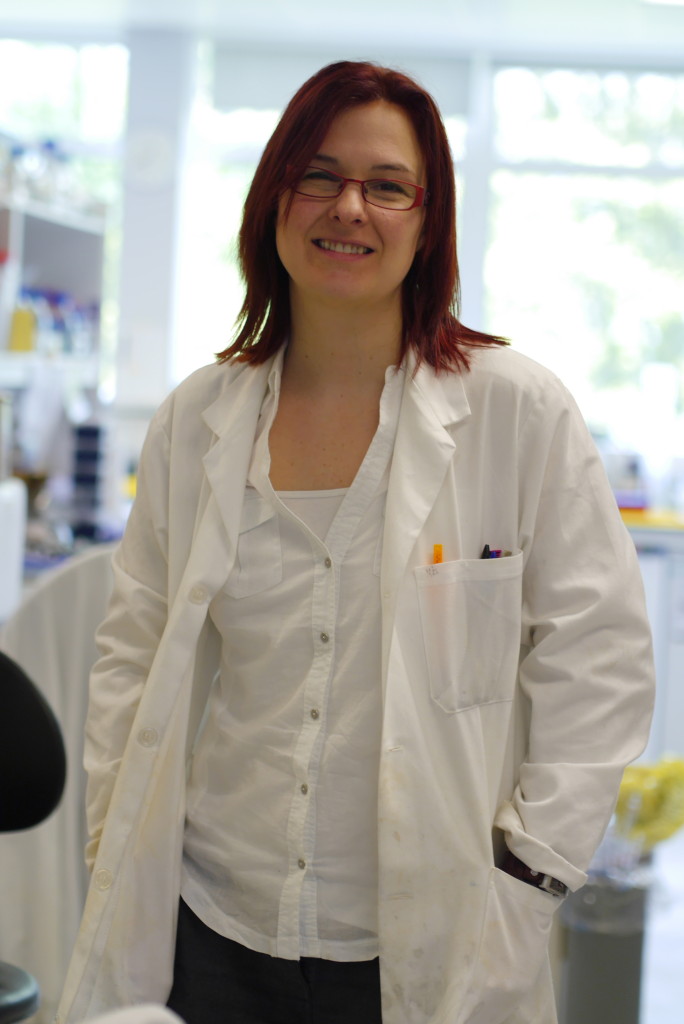

My trip to Birmingham University – more specifically to the School of Cancer Sciences – made my BRCA fund and awareness raising all the more real. Below is my interview with Dr Jo Morris one of the senior lectures as well as a Breast Cancer Campaign research fellow. Here is the post about my trip to understand the BRCA gene research progress.

Can you remember the day you decided to take this route with your research? I remember deciding that I wanted to work on something with teeth, a snarling real problem like breast cancer predisposition fitted the bill.

What are your short and long term work goals? I really want to ‘nail’ how it is that the BRCA1 protein actually works, how it acts to prevent cancer (the BRCA1 protein is the thing that the BRCA1 gene makes).

What makes you smile at work? Like every scientist –results! Finding something out today that we didn’t know yesterday. That’s just brilliant.

What makes a work day good? Lots and lots of results!

And a frustrating one? As you’d expect –no results, or conflicting results –that feeling that we’ve taken one step forward and two steps back.

How do you unwind after work? I find pulling weeds is so therapeutic.

How much contact do you have with international scientists in your field? At international conferences, we find out what the rest of the world is doing. Also on some projects we collaborate with international colleagues.

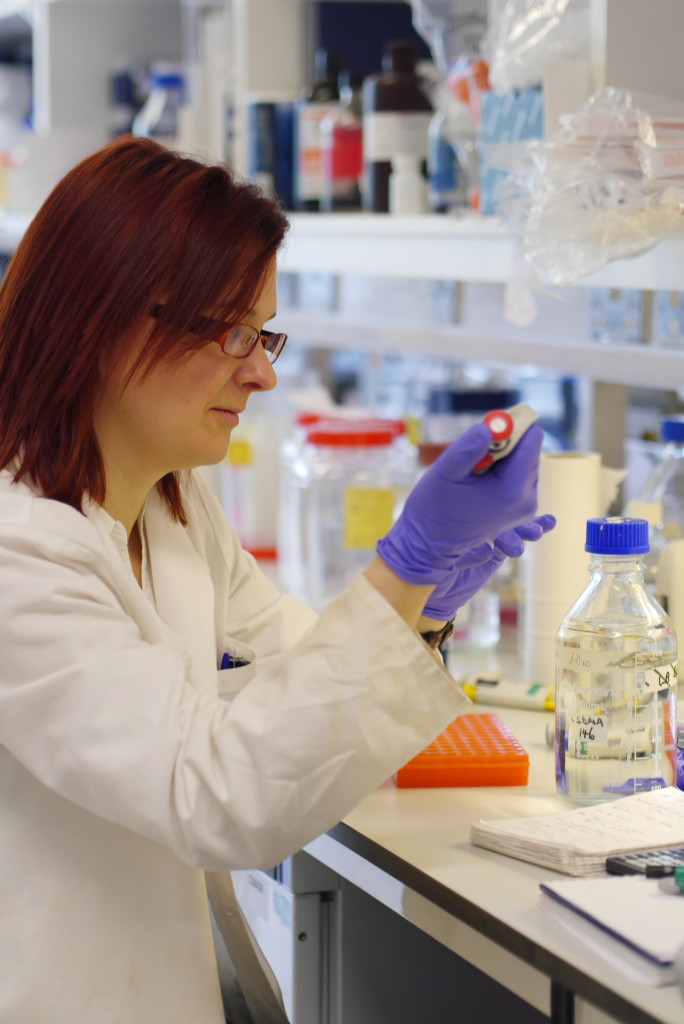

What was the most recent discovery your team made? We found that the BRCA1 protein is switched on in cells by the attachment of a little protein with a big-sounding name –SUMO. This tells us a little more about how this amazing protein works inside cells.

And what are they working on today? We are trying to find out whether the situation matters to the way the protein helps prevent cancer development.

Then I asked some questions I had been sent by other BRCA mutation carriers who belong to an international Facebook support group:

how do I find out my specific risk not the general statistics? At the moment risk is estimated as function of family history (how much disease is in the family –and is done through consultation with a genetic counsellor. This is an attempt to measure the amount of genetic predisposition in your family. We don’t have sufficient finesse in our understanding of the genetic ‘modifiers’ of risk to measure your own DNA and calculate the risk. However this is changing, and we are now aware of other gene changes that together with a BRCA change alter risk profiles. It may be some time before we are able to offer this information in the context of a genetic counselling environment.

What new research is being done to further understand the size of the risk?

This is ongoing research, rather than anything new. It is down to:

1) the identification of mutation in particular ethnic groups

2) the procedure and results of genetic testing

3) the incidence of breast and ovarian cancer and other cancers

4) the prevalence of cancer in BRCA patients with and without preventative measures

5) the survival after diagnosis and treatments and

6) clinical trials of new therapies effectiveness on BRCA cancers.

All of these will help understand the risk of particular mutations causing cancer and the development of the cancer.

For those who have had preventative surgeries, should we need any further monitoring? ie are those carrying the BRCA gene mutation more likely to get other cancers?

For those who have had preventative surgeries, should we need any further monitoring? ie are those carrying the BRCA gene mutation more likely to get other cancers?

The primary cancers associated with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation are breast and ovarian cancers, but there is evidence that a BRCA1 mutation may increase the risk of a woman developing fallopian tube, stomach, pancreatic, peritoneal and colon cancer. Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers have a higher risk of getting breast cancer and prostate cancer. The increased risk of getting these cancers in BRCA carriers varies with each type of cancer.

How long do you think it will take to correct the defective gene? This question carries with it an assumption. How do we know that correcting the change in the adult will make any difference? It is possible to do at the early cell stage at least experimentally. Importantly it is not clear whether it’s ‘safe’ to do it –frying to fix BRCA may cause more gentic problems than it solves.

If you’re going to try and ‘fix’ a single-cell (or 8-cell) embryo, and risk damaging it the question then arises whether it might be better to ‘chose’ an embro(or sperm or egg) that doesn’t carry the mutation (and not damage it). This, for many, is an ethical question.

How closely can your team look at the specific mutation and tell which cancers that person is at higher risk from. This is a big question and something that we’re actively looking into. Not only is it important for carriers of those changes, it also has the potential to tell us about how the BRCA proteins (the things that BRCA gene make) work. This is not easy but we’re working on it.

I am curious as to whether BRCA+ women/ men without children will be advised to use pre screened embryos (or sperm) which lack mutation when considering family planning. It’s probably expensive and controversial, but to eliminate passing of this gene… In July 2012 at the ESHRE (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology), Professor Willem Verpoest from Vrije Universiteit Brussel presented a study on the feasibility of pre-implantation genetic diagnoses (PGD) for BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. It does show that the practice is possible and effective.

Are there definitive UK guidelines on ooph age? NICE guidelines say that risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be deferred until the woman has completed their family (NICE, 2013). There are no specific guidelines as to what age a woman with a BRCA gene mutation carrier should have an oophorectomy, but it is recommended for the procedure to happen as soon as possible. The patients’ family history is important because if other breast and ovarian cancer sufferers in their family have be diagnosed at an early age, it may be a more urgent preventative measure.

how can we keep our local GPs updated as mine had no idea what BRCA was? There is an online GP notebook that has information about BRCA genes and includes advice on how to treat such patients. It also includes the NICE 2013 recommended guidelines on treatments and genetic testing. The NCI (National Cancer Institute) has information online about BRCA1 and BRCA2 and patient recommendations.

Here is more about my visit to see cancer under the microscope.